How it all began…

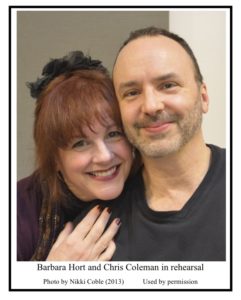

It began quite innocently, in 2012, with lunch and an ambush. My friend Chris Coleman — at that time the Artistic Director of Portland Center Stage in Portland, Oregon — invited me for one of our light lunches and lightning conversations. I adore Chris’s nimble mind and psychological orientation, so I happily accepted his invitation. It turned out that he was planning to produce Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street as his opening show for the 2012-13 season, and he wanted to ask me a question about the character of Todd.

“Why is it,” Chris asked, “that when Todd decides to kill the world in the song Epiphany, he says ‘I’m alive at last! And I’m full of joy!’? What makes him say that, when he’s just decided to slice open every throat he can lay his hands on?”

“Welllll,” I replied slowly, “I have no idea why Todd is feeling or saying those things. And I know even less about what Sondheim was feeling when he wrote those lyrics. But what I can tell you is why real people in situations like Todd’s are inclined to feel and say things like that. You see, when real people have been violated and incarcerated by repressive authorities, as Benjamin Barker was, they tend to become very depressed. In fact, they frequently report that they no longer feel alive. If people in such circumstances happen to find some new reason for living, even a vengeful and bloody reason, then a new energy flows through them. Usually, it is one of the elemental energies that a Jungian psychologist like me would call archetypal— the energies we see represented in symbols and stories that are ancient or universal. When an archetypal energy erupts in a person who has been deeply depressed, that person can feel reanimated, even resurrected. Sometimes the person is ‘resurrected’ by finding religion, or a similarly redemptive calling, as Ghandi and Dr. King were. But in other cases, the depressed person finds a darker calling, such as the wreaking of vengeance upon a world that s/he feels has earned whatever punishment s/he inflicts upon it. And so the person goes about that bloody work with a sense of righteousness and a weapon of choice — a gun or a bomb or, yes, even a razor. A man carrying a straight razor might, for example, see himself as a latter-day Michael the Archangel, seeking to bring justice to an unjust world with his righteous sword. People who have been ‘resurrected’ by a vengeful calling like that might well feel alive again, and full of something that is akin to joy. It is, admittedly, a terrible sort of joy. But the human psyche does not fuss about such distinctions under dire circumstances. The psyche just revels in the life force that has been denied and has now been returned, no matter the quality of the force. At least, that’s how it is for real people.”

“That makes so much sense to me!” Chris exclaimed. “Would you please come to our first day of rehearsal and tell that to my Sweeney Todd actors?”

“Oh, Chris,” I replied, assailed by doubt, “I don’t think your actors want a psychologist yapping at them on their very first day.”

“Yes, you must!” Chris insisted with a rising enthusiasm that began to draw glances from nearby restaurant patrons, “I’m sure the actors would love it! You have to describe all of that in person, because I can’t do it the same way!”

My reluctance to inflict myself on the unsuspecting cast was countered by my desire to accommodate the wishes of my dear friend. And besides (it occurred to me), the professional actors in Chris’s cast had probably been asked to do many things in their careers more odious than listening to a psychologist dither for awhile about depression and archetypes. So I said yes.

The actors in that production of Sweeney Todd were sixteen of the kindest people I’ve ever met. Or at least, that’s how I remember them. Far from rolling their eyes and yawning widely at me, they sat in rapt attention for my half-hour talk. And when I stopped talking, they inundated me with questions — about depression and trauma, about archetypes and characters (their own, mostly), about the narrative of Sweeney Todd, and a lot of other things that have now blended in my memory with all the other conversations I’ve had with actors over the years since that day. In that rehearsal, and in so many rehearsals since then, I felt as if I were lining up my little sandbags of psychological information, just as a Hoover Dam of actor curiosity was breaking over my head.

After the actors had questioned me for an additional hour in that first rehearsal, the stage manager observed that they had to move on, or they would never complete their table work. “But before you leave,” Chris asked me, “would you please agree to attend tomorrow’s rehearsal, so you can continue to answer the questions that come up?” Well, how could I say no? Even though I have always been certain that psychology was my professional calling, I have loved the theatre for as long as I can remember. The theatre has given such abundant treasure to me; it was an honor to give back if the theatre asked. So I attended that next rehearsal. And then I attended all of Chris’s rehearsals for every show he has directed in the years that have followed. I would have stopped attending if the questions — from Chris, his actors, and even production crewmembers — had ever stopped. But the questions have continued and so I have stayed, with gratitude and joy.

I love the curiosity that motivates theatre folk to search for anything that will help them tell their stories in a more authentic way. They are continually asking how they can better convey, in ways that are both compelling and believable, the shape and essence of their characters and narratives. The resource I have developed in answer to their questions is what Chris and I have come to call psychodramaturgy.

The practice of psychodramaturgy that Chris and I have developed has carried us through a host of psycho-theatrical adventures. From the travails of obsession, compulsion, and psychopathy in Othello, to the tensions between vision and reality in Dreamgirls. From the agonies of social injustice in Fiddler on the Roof and Clybourne Park, to the ambiguities of construing God in Major Barbara. From the anguish of terror and suffering in Astoria: Parts One and Two, to the challenge of reconciling with the human shadow in Oklahoma! From the dissociative consequences of trauma in A Streetcar Named Desire and Threesome, to the healing powers of personal narrative in Fun Home and Three Days of Rain.

Through each of these theatrical odysseys, our practice of psychodramaturgy offered the actors a resource designed to support their deeper journeys into the psychological realms of their stories. It is our hope that we can offer this resource to more actors, more directors, and more theatres, with the goal of enriching the art form that we all hold dear.