What Psychodramaturgy IS…

The fundamental definition of psychodramaturgy is “the exploration and articulation of the context pertaining to a play’s psychological domain.” This means that psychodramaturgy is the practice of offering to the actors and director a map of the psychological dynamics that are emerging in their manifestation of the play they are producing.

Note that I emphasize the word “their” in the previous sentence. I do this because the shape of useful psychodramaturgy will vary from production to production, depending on the artists who are telling the story. Every act of dramaturgy is, ideally, tailored to the team of artists who are creating the production. But immediacy and presence are especially important in the practice of psychodramaturgy, because the psychological information that will be relevant to the artists must be as vital and variable as the artists themselves.

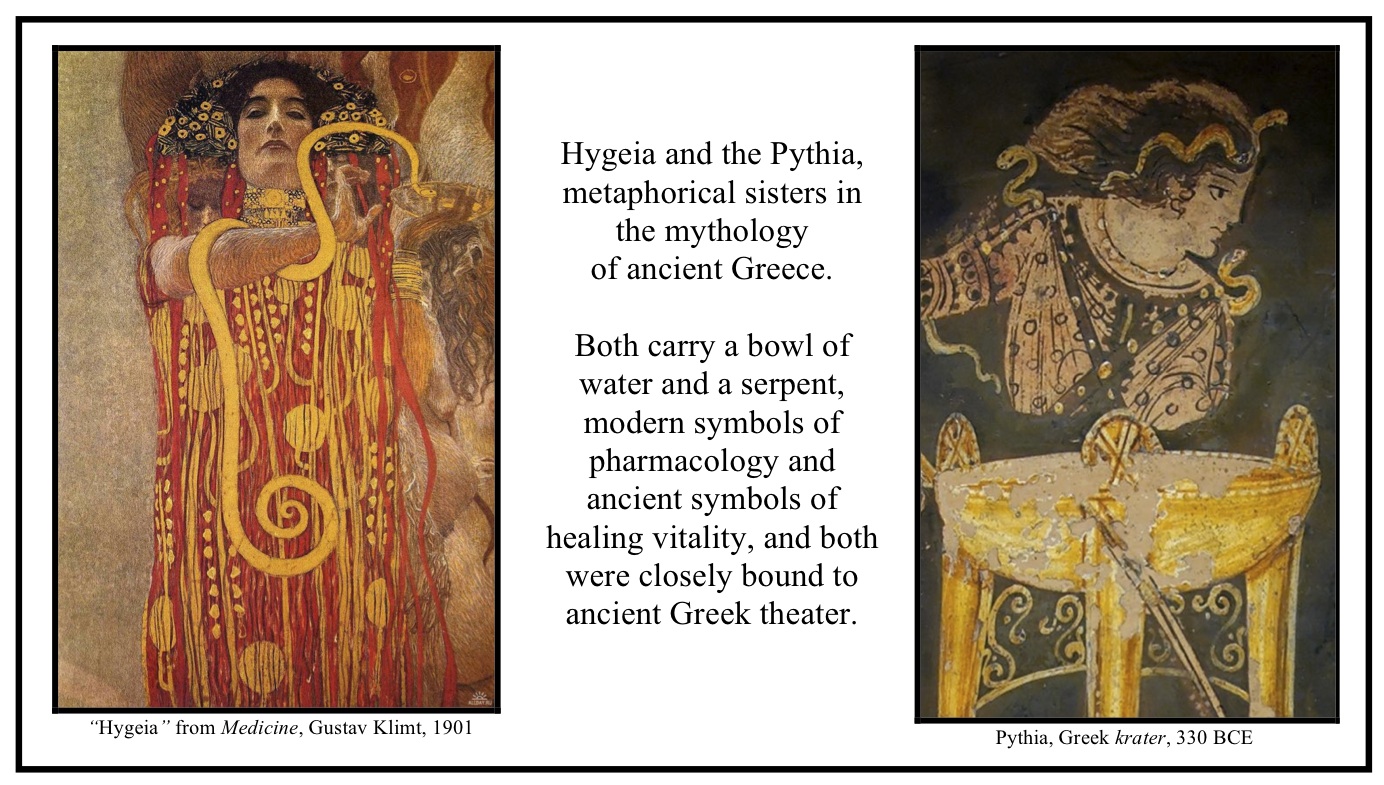

On the Home page, I observed that the ancient Greeks who invented what we now call theatre were well aware of the deep relationship between Thespis and Psyche. They built their theatres in their great centers of healing, and near each theatre, they built a temple to Hygeia, the goddess of good health (shown at left below). Hygeia was one of two mythic females in ancient Greece who were always depicted with a bowl of water and a snake. The other was the sybil Pythia (shown at right below), the priestess who delivered messages of life-changing importance in Apollo’s temple at Delphi.

The symbolic similarity of these two entities tells us that all activities invoking the Psyche-Thespis relationship, including the practice of psychodramaturgy, are best approached with Water and the Snake — that is, with the fluid immediacy of natural life force — the essential energies with which theatrical artists approach their work in the rehearsal hall and on the stage.

From this symbolic message left to us by the ancient Greeks, and from my years in the development of psychdramaturgy, I have derived the following principles of its practice. However, I strongly urge every reader to carefully study the information on the page “What Psychodramaturgy is NOT,” in order to eliminate any misconceptions about this new addition to the canon of theatrical resource. The information on this page will be worthless without those cautionary instructions. Okay, so here we go…

Theatre is a living art — immediate, ephemeral, incandescent, and fundamentally mysterious. Although I have often written short essays for the actors and creative teams on a production, it is most important for me to be present in the room when a play is being rehearsed, at least for some of the time, so that I can get a felt sense of the psychological dynamics that are coming to life in that production. We all know that a single script will take on very different lives, depending on its production. Even the change of a single actor can change the shape of a production’s psychological shape. My ability to offer information about “what real people do” depends fundamentally on the specific psychological elements of the story and characters that are coming to life in the rehearsals.

All good theatre artists know what it means to be present in the room and on the stage, but what does it mean to be present as a psychodramaturg? In the postdoctoral training I received from the Jungian analyst Marion Woodman (who herself had been a theatre artist), I came to understand that my ability to support the psychological processes I am witnessing is utterly dependent upon the quality of my presence as a witness. In Marion’s exercise “The Dance of Three,” we learned that every act of creativity (and healing) entails three forms of presence — 1) the Dancer (or Actor, or Creator), through whom the artistic(healing) energy flows, 2) the Mirror, who resonates with and reflects the Dancer’s energy and thereby augments the artistic(healing) process, and 3) the Container, who holds the Dancer, the Mirror, and their artistic(healing) space in a compassionate and protective regard.

During the years in which I have explored psychodramaturgy, I have come to feel that all three forms of presence are integral to its practice. In my presence as a Container, I witness the director’s and actors’ artistic process with a sense of protection and compassion. In my presence as a Mirror, I silently resonate with and reflect their creative energies, presumably augmenting them with that reflective resonance. And in my presence as a Dancer, I must myself be fully and authentically present in my psychodramaturgical role. If I am not, my inauthenticity will impede the flow of energy in the room. Indeed, if I am not completely present in all three of these roles, I will be unable find the shapes of the “real people” that can best serve the artists’ creative process.

Whether we are in a group discussion around the table or pursuing active rehearsal, and even when I am present in the room during breaks, I almost always wait for the director or an actor to request my input on a psychological issue. On rare occasions, when the discussion or process becomes jammed on a psychological issue — repeatedly or for a prolonged time (which could be as much as five minutes in rehearsal) — I will raise my hand subtly and then wait for the director to invite my input at a moment of his choosing. I have also passed a note to the director with a few words of explanation, and then spoken at more length if he asks me to. Similarly, when the actors are on break, I only offer input if one of them approaches me with a question.

Sometimes an actor will approach me at the beginning of the rehearsal process and ask me to “please speak up if you see something I should pay attention to during rehearsals.” In this case, I tell the actor that I only offer input when asked a specific question, so if s/he wants my input on a regular basis, s/he must ask for it as regularly as s/he wants it. I explain that I have no way of knowing when my input will be helpful, versus when it will intrude on their creative process. Only the actor can tell me that by asking me to speak. And I also tell the actors that there will be times when I will have no input to offer, because “what real people do” is often accessible enough that they will know the answer for themselves.

Once again, I’d like to believe that this energetic position is guided by our theatrical founders, the ancient Greeks. One of their most revered Muses was Polyhymnia, the Greek goddess of storytelling. It is fascinating that although she was the deity who inspired all great storytelling, Polyhymnia was commonly depicted with her finger to her lips, indicating the value of the sacred hush in the service of credible words.

It is my experience that the fewer words I use to make my psychodramaturgical point, the more effective I will be (the regrettable length of this website notwithstanding). Of course, this will be challenging to any aspiring psychodramaturg because it means s/he must condense the masses of professional knowledge s/he has acquired into psycho-summaries of astonishing (even appalling) brevity.

For example, I have been known to observe (to an actor’s advantage, I was told) that “The most successful psychopaths are seductive, rather than repulsive.” And later in that same rehearsal run, “Psychopaths only want to win. If killing is required, so be it, but that is not the psychopath’s goal. It is the sociopath who wants to kill.[1] For example, Putin is a psychopath, whereas Stalin was a sociopath.” My graduate school professors (and many of my clinical colleagues) would be horrified by these minimalist explanations, but psychodramaturgy has made me a believer in Chris Coleman’s principle that one should “Be brief, be bright, and be gone!”

[1] See, for example, Jack Pemment, “Psychopathy versus sociopathy: Why the distinction has become crucial,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 18, no. 5 (September-October 2013): 458-461.

A wise person doesn’t give the right answers,

a wise person poses the right questions.

~ Claude Levi-Strauss ~

When an actor approaches me with a question about her or his character, I always ask questions first, before offering any utterance that ends in a period.

Frequently, actors have asked me questions on the order of, “Do you think my character might have been [abused/neglected/traumatized/loved] as a child?” In response, I always begin with, “First, I’d like to know what you think your character experienced as a child? What do you know from the script? What have you deduced? Suspected?” Actors are intuitive wizards of the psyche, and they usually know far more than they realize about the character that is coming to life inside of them. They certainly know more about their characters than I do.

Once I have asked all the questions I can think of about what the actor knows about the character, then I usually find I have a selection of options for “what real people do, and what has happened to them, in situations that are similar to your character’s situation.” My goals are two in this case: 1) I want to respond only based on what the actor is feeling about the character, and 2) I want to give the actor a variety of psychological options that might pertain to the character so that s/he retains as much creative latitude as possible. I do this partly to serve the creative process, and also because psychology is still a rather inexact science, based as much on the psychologist’s talent for pattern recognition and symptom correlation as it is on irrefutable data. (Again the horrified gasps of my professional colleagues…)

And beyond that, the trait of a character is like any symptom — each one usually has several possible origins. For example, the trait that we call “psychosis” (which includes the seeing and hearing of things that aren’t there) can, in real people, variously be a symptom of severe depression, or schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder, or chemical toxicity, or posttraumatic stress. Or the real person displaying psychotic symptoms could simply be “malingering” — that is, feigning madness. Therefore, the actor playing Richard III, or Lady Macbeth, or Ophelia should be given as many of these “Real people who act like this…” options as possible. The actor can then decide (usually in consultation with the director) which interpretation of origin best fits the story they are telling.

Many psychological phenomena that we now define as the logical consequences of Fortune’s slings and arrows have historically been considered (and sometimes with tragic recency) to be the work of demons and deities…or simply evidence of “bad character.” Addictions, obsessions, compulsions, delusions, mood disorders, and hallucinations can now be traced to organic or environmental origins. But throughout the millennia preceding modern psychology, they were often deemed afflictions of supernatural origin. Interestingly, the gifted playwrights of character (Shakespeare, Williams, and O’Neill come immediately to mind) have frequently delineated a virtual case history of a character’s mental miseries, including their origins, even though those playwrights were writing in eras of clinical ignorance.

There have been several occasions (a beautiful production of A Streetcar Named Desire comes to mind) in which my offering about “what real people experience” (under circumstances of traumatic dissociation in the case of Streetcar) allowed an actor larger access to a character and the story. The story did not change — every word and nuance remained intact. But the additional layers of psychological understanding enabled the actor to reveal additional layers in Williams’ magnificent play, possibly because the actor could reach beyond the play’s original construal of “madness.”

Sometimes it is possible, and helpful, to articulate for an entire cast the core of a psychological phenomenon that is pertinent to everyone in the story. When that is the case, and Chris has asked for it, I have provided what I think of as a “shot glass” of the pertinent topic in psychology. Here, for example, is a two-minute “shot glass” on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from a recent production of Fun Home:

“Trauma is what happens when life throws more at us than we can handle. Usually, we break down the experience by breaking ourselves into pieces — or as a psychologist would say, we dissociate. This is how a healthy psyche survives the devastating shock of an overwhelming experience. The feelings from the memory go in one box, and the images go in another box, and we lock those boxes away from consciousness. Sometimes the whole experience goes in a box so that we can temporarily forget the episode and carry on with something like “normal” behavior. Those boxes are where the memories can remain untouched until the world feels safe enough for the boxes to be opened so the memories can return to life. Sometimes the memories stay in the boxes for a few hours, but sometimes they stay there for decades…like Alison Bechdel’s did. No matter. Our psyches, like our bodies, are always trying to heal, always trying to put things back together. So when our locked-up trauma chickens get out of their boxes and come home to roost, it’s like déjà-vu all over again, and the trauma comes alive again, along with the memories. That’s PTSD — posttraumatic stress disorder. Sometimes people find ways to sooth their trauma chickens, and sometimes they don’t. Doing something creative with the trauma chickens seems to be the best way to calm them down and eventually, to persuade them to lay eggs.[i] That’s what Alison Bechdel did…and so brilliantly.”

True, my professional colleagues would probably be appalled by this hot-shot of information about PTSD. But a shot glass is all we have time for in rehearsal, and in some shows, there are a lot of psychological issues to describe, with no time for lengthy explanations. And no need, really, because actors are very quick studies when it comes to psychological shapes. They need to be quick studies because some plays — well, a lot of plays — pose psychological challenges at every turn.

[i] See, for example, Kalsched, D. The Inner World of Trauma: Archetypal Defenses of the Personal Spirit. New York: Routledge, 1996 and Kalsched, D. Trauma and the Soul: A Psycho-Spiritual Approach to Human Development and Its Interruption. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Even in the beginning of our exploration of what we came to call “psychodramaturgy,” when Chris Coleman and I were probing the psychological shadows of Sweeney Todd (see “How It All Began”), it became apparent to us that some psychological phenomena were too complicated to explain in rehearsal. Nonetheless, Chris felt that an explanation of these topics could provide a foundation and framework that would be helpful to the actors. So he asked me to write short essays that he would make available to anyone in the company who wanted to know more about the psychological issues that were emerging in rehearsal.

And thus began the written portion of my psychodramaturgy — a series of essays invoked by the issues that were revealed in the rehearsal process. Frequently, these essays addressed the energetic dynamics that I mentioned earlier — what the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung called archetypal energies. These energies, similar to instincts, are hardwired into the human psyche, informing the primary thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of all people.

I’m not sure whether such essays are essential for successful acts of psychodramaturgy, but many actors say they find them helpful and interesting. So my guess is that they are beneficial, at the least. Here is a list of the essay titles, to give you a sense of how they have related to each production:

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2012)

- Archetypes and Archetypal Energies as Demons…and Dæmons

- Sacred Shattering: Surviving Trauma through Dissociation

- Understanding “Shadow” in the Wake of Trauma: Morality versus Dissociation

- Projection + Obsession + Sexuality = Apotheosis

- Dæmons, Demons, and the Art of Being Fully Human

- Cannibals, Vampires, and Social Injustice

- Vengeance, Forgiveness, and the Paradox of Heroism

- The Healing Power of Theater

Clybourne Park (2013)

- The False and Insatiable God of Anger

- Addicted to Perfection or The Botoxing of the American Soul

- Wounds and Words: The Impact of Emotion on Our Ability to Express Ourselves

- Affection versus Aggression: The Expression of Power as a Function of Status

- Grandiosity, Entitlement, and the Addiction to Perfection

Fiddler on the Roof (2013)

- Arguing with God: The tradition of righteous debate in Jewish philosophy

- Holding Off Terror, Holding Onto Hope: Life in the crucible of culturally sanctioned persecution

- Tradition, Tension, and Transformation in the Pale of Fiddler and Beyond

- Repression and Reverence: The Complex Status of Women in Jewish Society

- Meeting the Fiddler…On the Roof and in Our Lives

Othello (2014)

- Lethal Love: Examining the Agony of Ecstasy

- Ego and Equus: Seeking the Harmony of Mind and Body

- The Infernal “Or”: The Insufferable Consequences of Rejecting Ambiguity in Ourselves and Others

- Prodigy and Predator: A Profile of the Seductive Psychopath

- Mining or Declining the Treasure of the Unconscious Mind: A Cautionary Tale from Othello

Dreamgirls (2014)

- Life is but a Dream: A Few Important Facts about Dreams and Dreamers

- Everyone is Tone-Deaf (Somehow)…and Everyone has Perfect Pitch

- Dark Divinity and Sacred Flesh: Dreamgirls and the Rise of the Black Madonna

Threesome (2015)

- Trauma, Dissociation, and the Audacity to Heal: Walking with Dante through Hell and Beyond

- An Influence Suffered but Seldom Seized: The Plutonian Power of Complexes

- Seduction, Abduction, Possession, and Redemption: The Menace of the Complex and the Model of Persephone

Three Days of Rain (2015)

- The Water of Life: Drought, Flood, and Flow in Human Emotion

- The Building of Unimagined Bridges: Destiny, Audacity, and Our Search for Identity

- What is the Truth that Sets Us Free? Personal Narrative as a Life-Saving Work of Art

Ain’t Misbehavin’ (2015)

- Matter Over Mind: The Secret Gospel of Fats Waller

- Dreams, Audacity, and a Handful of Keys: Irrepressible Revolution in the Music of Fats Waller

A Streetcar Named Desire (2016)

- Stereotypes, Stigmata, and the Struggle to Know Oneself: Riding the Perilous Rails of A Streetcar Named Desire

- Obsession, Compulsion, Addiction, and Perversion: The Four Horsemen of Trauma’s Apocalypse

Astoria: Parts One and Two (2016-2018)

- Pioneer Stories, in the World and in the Soul

- There and Back and Everything in Between: The Archetype of the Journey

- Leaders and Followers: Those Who Don the “Hollow Crown” and Those Who Defer to It

- The Angel of Death and the Bedevilment of Life: Trauma, Tragedy, and the Courage to be Human

- Many Ways to Shatter, Many Ways to Heal: The Permutations of Trauma

- Anger, Anxiety, Addiction and Apricots: The Survival Strategies of PTSD

- Visions and Values…versus Validity: The Redemption of Trauma through the Quest for Truth

Fun Home (2017)

- Adoration, Ambition, and Anguish: The Merciless Mirror of Narcissism

- Anxiety and Antiques: Mining the Treasures of Dissociated Memory

- What is the Truth that Sets Us Free? Personal Narrative as Life-Saving Art in Fun Home

Major Barbara (2018)

- Debating the Nature of God: The One and the Many, Inside and Out

Oklahoma! (2018)

- Homesteading the Earth of Our Souls: Pioneering in a Land of Shadow and Light

Anna Karenina (2019)

- The Formula for Happy…and its Failures in Anna Karenina

A Doll’s House and A Doll’s House, Part 2 (2019)

- Down (and Back from) the Abyss of Personal Transformation in A Doll’s House and A Doll’s House, Part 2

- Marriage and Prostitution in the Patriarchy: Illusion and Confusion in Negotiating Power and Love

Twelfth Night (2019)

- Love, Madness, and Transformation in the Land Beyond Death: Journeys to Redemption in the Far Country of Twelfth Night

- The Solar Blaze of Truth and Foolery: Tales of the Wise Fool

Much Ado About Nothing (2022)

- All of Life’s a Stage: The Play of Our Parts, Light and Shadow

- Shakespeare and the Natural Order: The Divine Heresy of Humanism

Hotter than Egypt (2023)

- Living While Dying: The Art of Embracing Growth All The Way Through Life

- The Deadliness of Despair and the Challenge of Nurturing Hope…No Matter What

A Little Night Music (2023)

- Apotheosis or Addiction?: Obsession as a Pathway to Heaven or Hell

- Sondheim, Like Shakespeare…Paganism Between the Lines

Rubicon (2024)

- Reanimating the Body as a Core Life Value: Love vs Logic in the Story of Rubicon

- Emergent Feminism and Sacred Prostitution: Unearthing Hidden Treasure in Rubicon

- Living Dreams of Destiny: Alice in Wonderland, Betty in Rubicon